Despite our love of UK animator Stephen Irwin’s work stretching back to our print days, we’ve somehow neglected to sit down with the director to find out more about his singular style of filmmaking. With his new short The Obvious Child hitting Vimeo’s VOD service last week we decided to immediately rectify that situation and find out more about the motivations which have driven Irwin to evolve as a filmmaker over the past decade.

Your animation style has progressed through various incarnations throughout the years, what do you see as the driving force behind the evolution of the look of your work?

Boredom! I made The Obvious Child in colour because I’d been working in black and white for ages and needed a change. It takes so long to make these things, because it’s just me on my own, so I need to find a new approach or a new way of working with each one. I never know how I’m going to achieve a certain look or style when I begin so it means I have a series of problems to solve. It helps keep it interesting.

Alongside the development of style, there’s been this increasing level of darkness which permeates your pieces, what is it that draws you towards these bleaker narratives?

I honestly don’t know. I don’t find them that disturbing but I guess I’m so close to the films by the time they’re finished I can’t really judge it properly. It’s interesting seeing the audience’s reaction after festival screenings. Some people seem genuinely offended which I find amazing. Getting a reaction either way pleases me. Not because I want to upset anyone, I just like that they have an opinion on something that I’ve spent so long making. Even if it’s negative, and even if they call it “stupid” and “incredibly stupid” in the same sentence.

Some people seem genuinely offended which I find amazing. Getting a reaction either way pleases me.

Your stories have a tendency to not only unfold narratively but also play with the form of animation itself such as in Horse Glue and The Black Dog’s Progress. Is that driven by the stories themselves or a desire to work outside of traditional constraints?

With The Black Dog’s Progress it was driven by my application for the Animate Projects commission. It didn’t have any of the flipbooks and spatial narrative aspects in the first draft. Animate weren’t interested in straight narrative films so it pushed me to develop it in a different way, and it was an extension of what I’d been doing at St. Martins. I tried to push it further with Horse Glue but that turned into a failed experiment. I got too obsessed with the idea of telling two stories at the same time, and in the same frame, and it never really worked.

You’ve created pieces for BBC New Music Shorts/Warp Films (Dry Lips) and Channel 4’s Random Acts series (Hidden Place), do these commissioned films differ in approach to your own self-initiated works?

Yes, because you first of all have to explain what you’re going to do and how you’re going to do it in order to get the commission. With my own films I tend to make things up as I go along to certain degree. I always write a script, make a storyboard and an animatic, but I know things will likely change as it comes together and I’m free to change what I want. The endings aren’t usually decided until I’m well into production because I need to see how the thing looks and feels as it comes together. When someone gives you money to make a film they understandably want to know what they’re getting so there are more constraints from the outset.

What sparked the idea for your tale of a devoted rabbit and an angry girl trying to get her parent’s body parts to heaven?

The initial idea was to make a film about how confusing religion can be for a child (in my case Catholicism), so her attempts to get her parents to heaven was just an extension of that.

Despite your work always having an overall cohesive look, the frames are often constructed using a variety of animation techniques. What were the methods you combined this time?

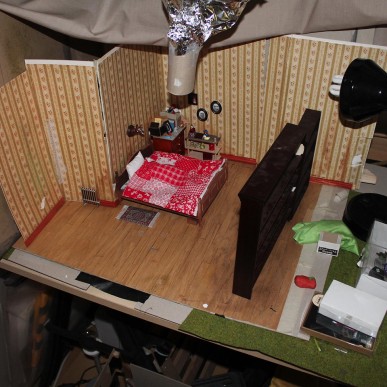

The backgrounds are miniature sets that I shoot at maybe 12 fps, adding little bits of movement to the grass, leaves, etc. The characters and other bits are 2D drawn animation, coloured with watercolours and scanned and assembled in Photoshop. Then everything is composited and animated in After Effects. I started using miniature sets combined with the 2D characters with Moxie in order to create more depth and to have a bit more to play with. My favourite part of making the last few films was physically constructing the sets and getting my hands dirty.

Similar to Ragga Gudrun’s deadpan narration in Moxie, Ron Masa gives this great halting delivery narration which feels a perfect fit for The Obvious Child’s glitchy visuals. How much of that came from your direction in the read verses the way you treat the narration in post?

I use a text-to-speech computer voice as a temporary narrator right up until the final edit (so maybe a month or two before finishing). This is so I can change and add lines while I’m animating and editing. I don’t want to have to keep going back to the narrator every time I change something, and I tend to change the text a lot as I go along. I got so used to the computer voice making this film that I sent it to Ron and asked him to follow the speech pattern and tone as much as he could. I also cut his narration up quite a bit in the final edit and reassembled it to make it sound unnatural and unpolished. With Raga, I gave her a bit of direction with certain lines but she did it perfectly in a couple of takes and there wasn’t much to change.

Zhe Wu has crafted some of my favourite animation sound design in the past such as for Joseph Pierce’s The Pub and of course Moxie for you. How do the two of you work together on projects?

I put together a very rough sound edit as I go along. Mostly music, but also some basic sound effects. We meet and go through the film a few times as it’s coming together but she doesn’t start work on it until the end and the picture is locked. I love watching it for the first time with a proper sound mix. The difference between my rough mix and her version is huge. You see the film with fresh eyes at that point and I usually want to start tweaking shots and scenes (which must really annoy her but luckily she’s a very nice person!).

I love the “personal journey into the art of animationing” you take us through in The Obvious Child Making of video. What made you take that approach to the BTS explanation and how much work was it to put together?

I needed something to work on just after my son was born. I didn’t have the energy to animate anything properly in that first month or two, so I put this together whenever I had a minute. I had all the footage so it was just fun to play around with the edit and make something dumb. I find makings of a bit ridiculous, especially for shorts, but at the same time I’m really interested in how other filmmaker’s work. I love seeing their process, their basic set up, and the kind of equipment they use. So people might find this interesting in parts. Or not.

The Obvious Child was funded through the Rooftop Filmmakers Fund and screened last year in their Dark Toons programme, how did that process work? Were Rooftop Films subsequently involved in the decision to release the film on Vimeo’s VOD platform?

They have a brilliant filmmaker’s grant scheme that is open to anyone who has had their work screened at one of their events. They weren’t involved in the decision to put it on VOD. That was largely due to the fact that I needed to geoblock it in certain territories because of a distribution contract. And partly because Vimeo invited me to put it up on there and kindly gave the PRO membership. And because I need money to buy nappies for my son, otherwise I’ll have to use plastic bags and newspaper.

What will we get to see from you next?

A music piece that’s in the early stages. And a new film is written and ready to be made.